From Adrienne Rich’s “Images for Godard”:

[…]

the mind of the poet is the only poem

the poet is at the moviesdreaming the film-maker’s dream but differently

free in the dark as if asleepfree in the dusty beam of the projector

the mind of the poet is changingthe moment of change is the only poem

(1) Picking up immediately where I left off:

In late June I celebrated six years of living in Toronto. I finally got off multiple medical waitlists, which concluded a protracted breakdown caused by the waiting—this is not a complaint but a fact about the nature of gender-affirming healthcare in Ontario. I made my way back into my body by August. It is fall, I am happy and having equally silly and serious ideas, which means my mind is operational again.

Between August and October Isiah and I were in Los Angeles, then Paris, to make a movie. I'd never spent much time in Los Angeles, and I'd never been to Paris. In each city I asked those we met to tell me about their favourite local cinemas, from childhood to the present. With this information in mind we tried to punctuate our days with as many movies as possible.

(2) In Los Angeles:

Isiah, Charlotte, and I stayed in Cypress Park. Much like in Jacques Rozier’s Near Orouët (1971), we spent the week cackling and drinking and running and rolling around. At the New Beverly Cinema I attended a double feature of Brian De Palma's Blow Out (1981) and Snake Eyes (1998). My estimation of Quentin Tarantino—who I really only respect as a serious admirer of minor De Palma films like Obsession (1976) and Raising Cain (1992), and as the owner of this cinema—was significantly raised by the quality of the New Beverly’s popcorn.

Blow Out and Snake Eyes are two crystalline depictions of a nation turned against its own people. Between the two one senses a sharpening of the knife, a leap from identifying categories to naming names. Blow Out is about two innocent working-class Americans trying to escape, through nothing but a pure belief in truth, the destiny of a forgettable death covered up by the government. Snake Eyes dares to be even more specific in its depiction of political corruption, presenting the American government as a brutish corporation willing to do whatever it takes to protect its lucrative alliance with Israel. It is an impressive exactitude, considering US-Israel relations serve as mere exposition at the very beginning of The Fury (1976). I use the word impressive to contain the accomplishments of this film within a very particular rubric. I had a good time.

(3) A brief break in Toronto:

Scénarios, and Exposé du film annonce du film “Scénario” (Jean-Luc Godard, 2024): Together these two posthumous films by Jean-Luc Godard (who appears to be shockingly quick-witted and alert, and who I only then realized I miss very much) serve as an ode to the joys of preproduction. The pleasures of the scrapbook and the note cards, the giddy excitement of excavating memories—of specific frames and cuts, turns of phrase, brush strokes—and locating in them deep wells of inspiration. The rhyme between Godard’s declaration of a seemingly incomplete work to be complete and the decision to die via assisted suicide concludes his oeuvre on a wonderfully vicious assertion of autonomy. To the very bitter end, he refused to be told what to do.

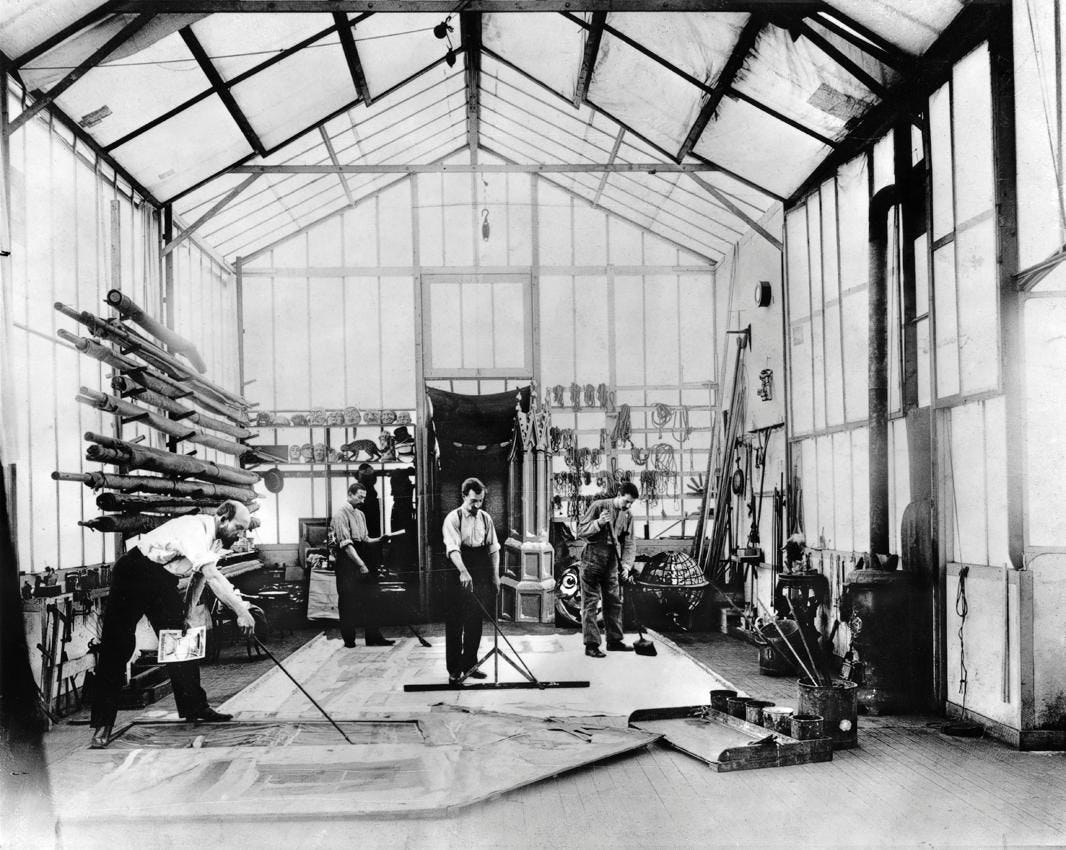

Georges Méliès (left) at his Star-Film studio in Montreuil, circa 1900.

(4) A few museums in Paris:

The two of us stayed in Bercy near the Cinémathèque Française, which of course houses the Musée Méliès. These two floors (which consist of notes, letters, posters, early cinematographic machinery, and so on) are a touching emblem of the great work Henri Langlois dedicated to the active preservation and stewardship of Méliès’s legacy, as well as—and this is especially crucial—his livelihood.

At the Musée Picasso I took many photos of hands, feet, breasts, and genitals (triangles, squares, squiggles, circles). One of my favourite Picasso pieces, which I was so pleased to encounter in person, is a sculpture from 1909 called "Apple." It’s an unimposing little plaster orb with rectangular ridges, reminiscent of prehistoric sculpture and the steep spiral staircase of a mountain village where the artist once lived. The works of Picasso that inspire me most are the seemingly embryonic ones: the vases and plates constrained by formal and material limitations, the studies scrawled before the ideas are stretched to fit a bigger frame, and the etchings.

A matter of personal preference. I prefer things that are shabby, shaggy, and extremely stark, with no boundary between finished and unfinished. I decided that maybe I find Picasso too finished, ironic given his being against the use of varnish. Lightness of touch only reemerges in the leaking and lumpy final paintings, which are bereft of self-consciousness and bursting with the lust of a late Antonioni film. There are some especially ugly frames at the Louvre, where bright ceiling lights refract off of very finished and perversely large French nativity scenes. I never fully understood humankind's desperate need for the historical intervention of impressionism until I walked through these halls.

I asked Isiah, if you were Thomas Crown in The Thomas Crown Affair (the 1999 remake, of course), which painting would you steal from the Louvre? Without hesitation, Isiah said either Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's The Turkish Bath or his Grande Odalisque. The Ingres paintings were hardly acknowledged by the museum visitors. Isiah and I joked that no one would notice if they disappeared, which is a shame. There is a complete disregard for the supposed logic of human anatomy that makes Ingres's portraits prone to surprising appearances of genderfluidity—Adam’s apples, deflated breasts, elongated limbs, etc.

(5) A few cinemas in Paris:

In Paris there are as many cinemas as there are bedazzled McDonalds and pristine Burger Kings. Notably many of the films playing across the city were American films that I’d never had the opportunity to see on a big screen: My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Poltergeist (1982) at Écoles, Dog Day Afternoon (1975) and Gloria (1980) at Christine. A great time—too great, in fact. I was bloated with revelations. I did also see Je tu il elle (1974) at MK2 Beaubourg and Masculin Féminin (1966) at La Filmothèque du Quartier Latin, but watching French films as someone who does not understand French is just me indulging a sick desire to be an unwelcome spectator jolted about by the image. Looking over a list of autumn produce on the flight I realized that I was ready to go home, buy some kale, and grow out my hair like River Phoenix.

Pablo Picasso, Sculptor and Model Looking at Herself in a Mirror Propped on a Sculpted Self Portrait, 1933.

Updates:

He Thought He Died is now available to watch online.