March 2020

Everything proceeds as usual, both planned and unplanned.

To be a bit too rough and direct, and I put myself under some scrutiny in doing so, I’ve become tired by the standard of relevance and repute, contingent upon trends, that determines what is or is not a worthwhile subject.

An example: On any day one may mention Naomi Kawase’s Hanezu, a 2011 film that superimposes a Nara-set love triangle onto the mythic formation of Japan’s national identity, that I quite like but have yet to write about for any publication (I am, however, not in a rush). So, tell me whether it fits these criteria: Did Naomi Kawase die on this day? Is it her birthday? Is it anyone’s birthday? Was the film released today, or five, ten, fifteen years ago today—not an unsightly number like two or thirteen, and if it is thirteen, shall we round it out to a “decade”? Is the film part of an ongoing or forthcoming retrospective or screening series, preferably one at a repertory cinema in a major North American or European city, and not just a matinee screening at a multiplex in Cupertino, California where only immigrants would go, and not just Wednesday night at my house? Is the film the subject of a book that was released today? Did Naomi Kawase receive some sort of big festival award recently? Did Naomi Kawase release a film recently, in particular one that received a United States theatrical run and opened in New York City? Is Japan’s national identity, or love triangles, or both, a hot topic related to a current event?

I turn the lever on the slot machine and wait. I take my coins and make do. I hope to do a damn good job and not just to do my job, if you know what I mean, though that does not mean that I always succeed. I hope to develop and prove a thought or theory that confronts the history of cinema whatever the film, whether a CGI-animated children’s film or Oscar bait. And still, even as I try to indiscriminately take on titles to review, I will not retire the argument that fighting on that front would be easier if the demands of my profession did not so closely overlap with those of copywriting or developing marketing for publicity, if I did not have to take into consideration how this-or-that cinema has a partnership with so-and-so’s publication or distribution company, or a filmmaker that is friends with the editor who might be upset if I say something mean. I worry that these very mundane circumstances—and the resulting banality and complacency in quality—has misled many writers to a point at which they are intellectually unprepared for crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic. (Of course, financially—and therefore emotionally and physically—as well.)

What shall I write about, we collectively wonder. Birthdays and death days until there are no more births and we all die? Frequently, I am asked why I cannot write about any movie I want. That has rarely been the case, but the actual question is why I cannot say what I want about any movie, even the assigned ones. The issue is actually three-fold, glued together by low wages: First, a co-dependency on industry events (repertory theatres, theatrical releases, international film festivals) is fostered by publications that operate as publicity vehicles. Second, that co-dependency festers among writers who do not challenge it as a workplace hazard that inhibits the very criticisms one sets out to produce as critic. Third, this co-dependency then becomes a crutch: writers themselves will blame such circumstances for their ideological or technical compromises, and for why they must resort to shallower pools of thought: “I can say what I want about any movie, so long as I don’t write this or that; that is the way it always has been, and I don’t want to question it or I will lose my job.” And once these places crumble, the writer turns up empty-handed.

Many writers are considered disposable by publications because they produce disposable work, because they are pressured to produce disposable work (and are edited with the assumption that it is disposable work, setting you up for failure by providing useless feedback or by removing the actual criticisms of the critic) with a small check hanging over their heads, because most writings about movies have to be disposable so as to not pull at the seams of the fabric, so as to not set it aflame.

Maybe an executive at a distribution company, a festival or cinema programmer, or the editor of a film magazine, might find themselves married to the market with no room for an out, but never should a critic find themselves in such a bind. I don’t want to write with only the word bank of a press release to fill the precious space I’d otherwise use to challenge what surrounds me. A divorce is both necessary and possible, for the sake of new theories, free speech, none of which have appeared on my radar ever since this disease has taken its hold on the film industry. Depending on how you look at it, it is week two or four, or maybe month three. Websites have become filled with content as a coping mechanism, and coping mechanisms as content. Articles on how film industry professionals are reacting to the crisis, recommendations for things to stream while in self-quarantine, twenty reviews of Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion. But where are the theories, the diagnoses of crisis? Why, for instance, is public access to films screened at festivals—from avant-garde shorts to restorations and features—only now a priority, now that the threat of death is imminent to those who might never afford to attend a film festival in their lives? Or why have we yet to weigh the irony in that the last two winners of the Palme d’Or have been films about vulnerable families living in utter poverty, and that this year’s Cannes Film Festival took nearly a month to negotiate its indefinite postponement, unable to determine whether exposing thousands to the virus is worth the risk?

What is missing are polemics that seize upon a most opportune time for overhaul. My partner Isiah Medina reminds me of the journal Screen, and its longstanding commitment to high theory. I also think about the late Chuck Kleinhans’s “Images after 9/11” in the Fall 2002 issue of Jump Cut, in which he addresses the “media problem” of the Bush administration—which images were present, and which were absent.

During this limited window, there was actually some presentation of the facts of U.S. imperialism, of U.S. support for dictators and military regimes around the world and how the government works in the interests of transnational corporations. But the discussion rapidly disappeared, and the images were not present. Americans don’t want to think about these issues which are best represented by the effects: dead and maimed victims of military actions, starving children, etc. Instead we ended up with images of Afghanistan: women shedding their burkas and reading books, markets selling posters and music from Bollywood films, gun-toting warlords in quaint local costumes meeting with formerly exiled politicians wearing western business suits.

I tell people that it is too early for conclusions, though a couple of predictions are easy to make. It is an undeniable fact that nothing will be the same after the pandemic de-escalates—it will not end, at least not in the way that many expect the virus to be banished forever. The film industry, however, will announce a sort of end to the disease, and everyone will attempt to move on very quickly, business as usual. Festivals will re-schedule and introduce a backlog of films that only those who can still afford a flight and a hotel for five to eleven days in Cannes, Locarno, Venice, Telluride, and Toronto shall be able to see. Some movie somehow will win a special Palme d’Or, and everyone will tweet about it, calling it the first post-Corona Palme at the first post-Corona Cannes. Some filmmakers will get sick, some won’t recover. We’ll shake our heads and mourn them with retrospectives once the cinemas open—fingers crossed behind our backs, we might even hope they do die so we can host even more screenings, as it would encourage more cinema attendance. A cohort of professionals will write an open letter to everyone in the film industry encouraging unity and friendship now that troubled times have past.

Publications will recuperate from covering streaming for months with overcompensating, sentimental essays on a golden renewal in our appreciation for the theatre experience, or for kissing in the theatres, or for holding hands at the Coronavirus-inspired series of movies playing at an overpriced repertory theatre in a city where the attendants of said theatre can barely afford rent. These articles will be written by freelancers with no healthcare who will receive a one-hundred dollar check in the mail five months later, which might help pay for a two-thousand dollar medical bill. A large number of these writers will quit (unless their publications shutter first) under the pressure of financial difficulty and the stubbornness of journals and magazines that do not welcome anything outside of the familiar format. They will join the thousands of theatre workers who’ve already been laid off. And at that point, many of us will be scratching our heads and wondering how, even after all those hours sitting in our homes with nothing to consider except our own thoughts, we still don’t have anything new to say about the movies.

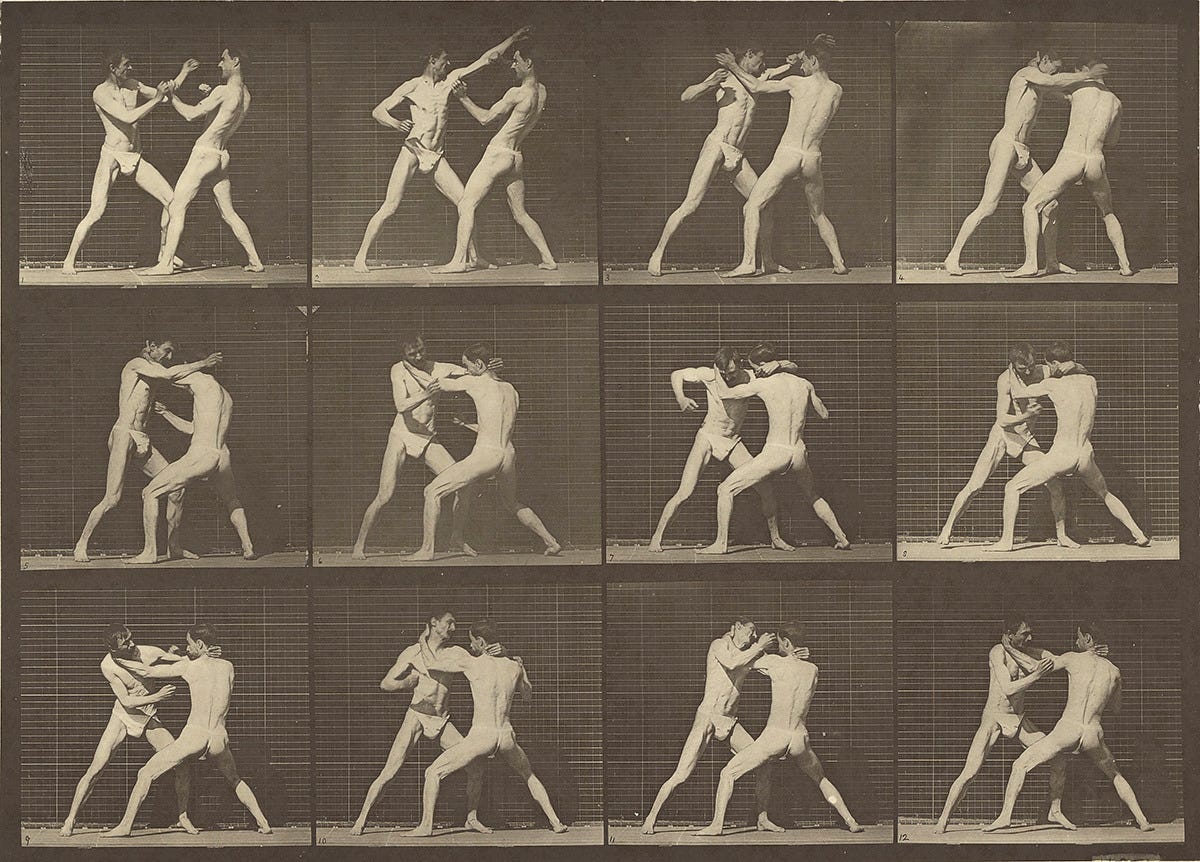

Edward Muybridge, Two Men Boxing, 1878-1879.